Abstract

The new Direct Acting Antivirals (DAA) have revolutionised the treatment of hepatitis C virus (HCV), replacing interferon (IFN) regimes which are known to cause adverse events with lower success rates. However, as these are relatively new drugs, all adverse events in the heterogeneous population outside of a clinical trial environment have yet to be determined. We report a case of newly diagnosed Pulmonary Hypertension (PHTN), where completion of treatment with Sofosbuvir (trade name Harvoni©) coincided with acute onset of PHTN. This case adds to the growing evidence suggesting a causal relationship between Sofosbuvir and PHTN. A prospective study would be required, as the data is often confounded by lack of preliminary right heart studies and confounding clinical factors for the development of PHTN.

Abbreviations

CT: Computer Tomography; DAA: Direct Acting Antivirals; DANI: Direct Acting Nucleotide Inhibitor; HCV: Hepatitis C Virus; HIV: Human Immunodeficiency Virus; ICU: Intensive Care Unit; IFN: Interferon; NS: Non-structural; OSA: Obstructive Sleep Apnea; PHTN: Pulmonary Hypertension; POH: Portal Hypertension; RHF: Right Heart Failure; WHO: World Health Organization.

Case Presentation

A 47-year-old man presented to the emergency department following a syncopal episode. Six months prior he had completed a course of Sofosbuvir and Ledipasvir (Harvoni®) for treatmentnaive genotype 1A HCV, with successful viral clearance. Past history included presumed Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA) and Right Heart Failure (RHF) (6-month history of progressive exertional dyspnea (WHO functional class III) and peripheral edema). He was a current smoker (20 pack-years), chronic alcohol user (12 standard drinks daily/20 years) and known intravenous drug user.

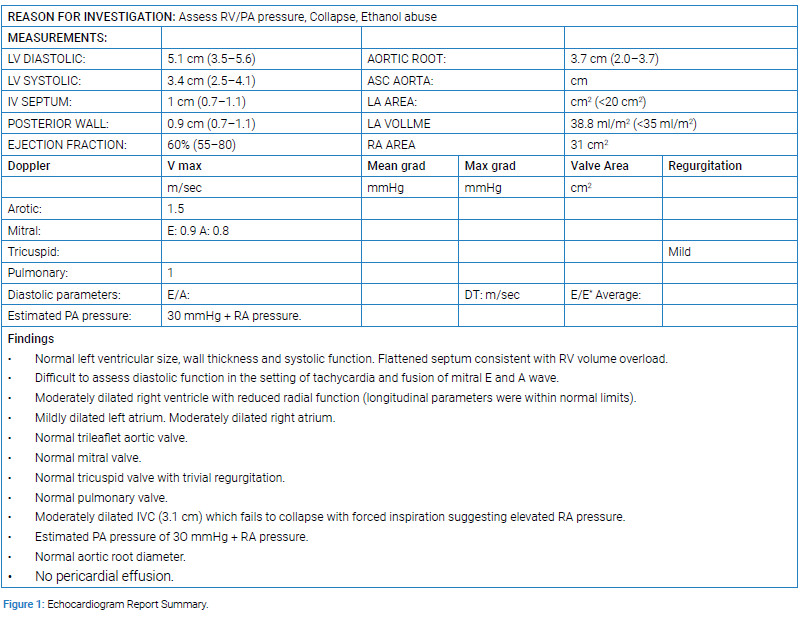

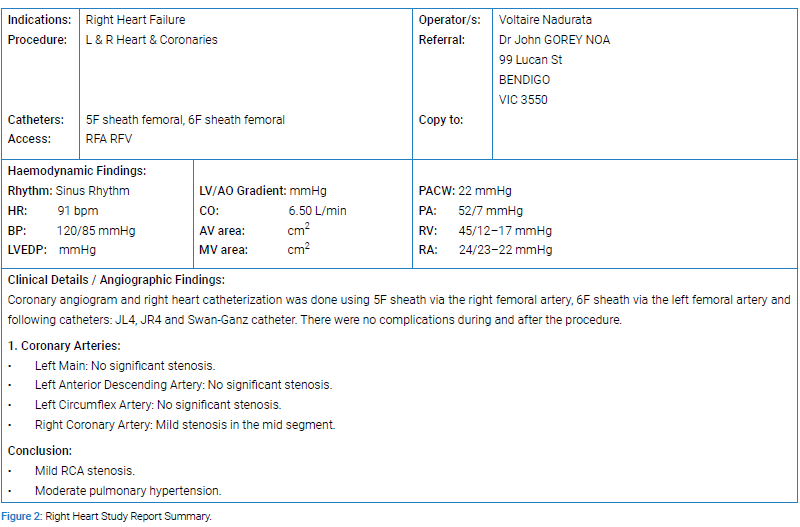

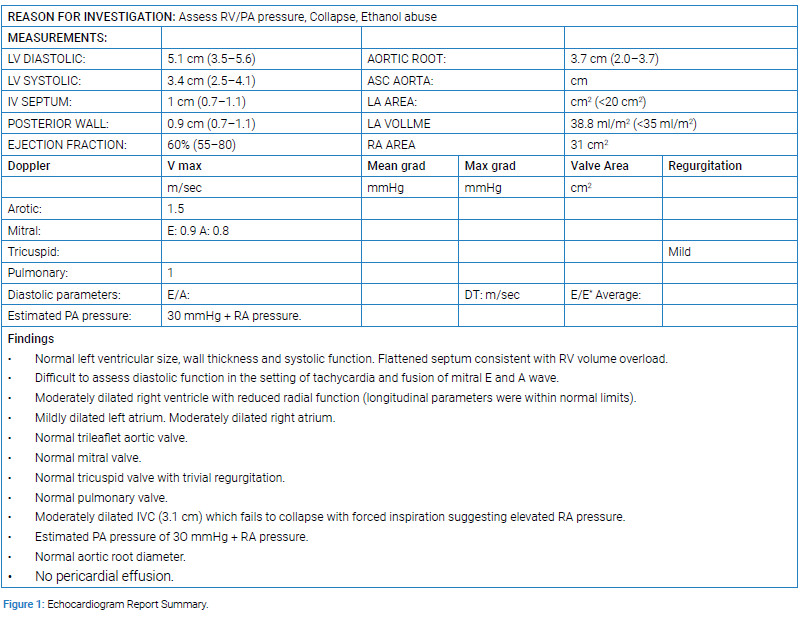

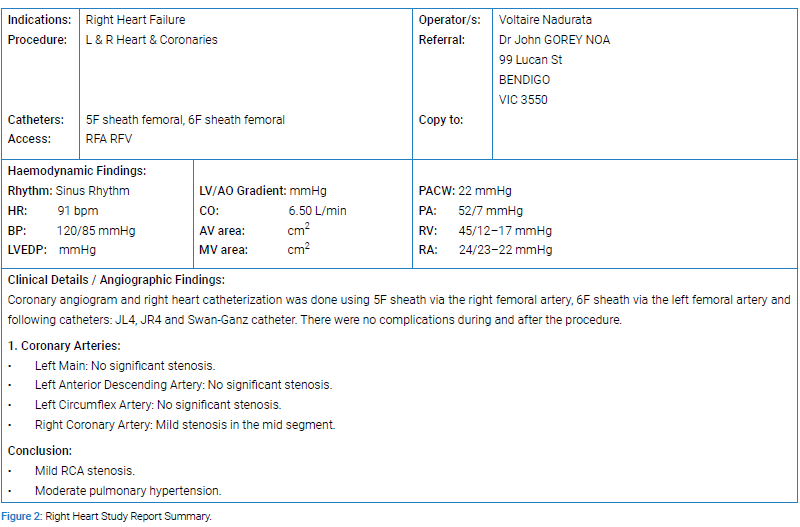

He had clinical features of acute on chronic type 2 respiratory Failure and florid RHF. Transthoracic echocardiogram and right heart study demonstrated severe PHTN according to gold standard grading classification for PHTN by the American Society of Echocardiography (Figure 1,2) [1]. His left ventricular function was normal. CT pulmonary angiogram, liver ultrasound, HIV serology and autoimmune screen were all unremarkable.

He was subsequently admitted to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) for treatment of his RHF and presumed obesity hypoventilation syndrome with diuretics and non-invasive ventilation respectively, resulting in clinical resolution of his acute decompensation over two-week period. An outpatient appointment was organized for investigation of OSA following hospital discharge which the patient never attended. Follow up after a year noted he had never showed up for any further review and he had subsequently passed away.

Discussion

Renard et al. was among the first to report a link between sofosbuvir and the development of PHTN, supported by Savale et al. who each reported three patients developing symptoms 1.5 months–7 months following DAA completion [2,3]. These patients presented with comparable clinical parameters and within the same time frame as our case. However, each of these patients had a PHTN-related comorbidity of portal hypertension (POH), HIV coinfection and/or liver cirrhosis. This manuscript demonstrates a patient without POH or co-infection with HIV, but one complicated by OSA, alcoholism, and smoking, as potential confounders for the development of PHTN. This point also highlights the difficulty of retrospective analysis in these cases to discern the real relationship between DAA and PHTN.

Sofosbuvir is a Direct Acting Nucleotide Inhibitor (DANI) which, in combination or alone, is the recommended first-line treatment for chronic HCV, as per both Australian and American consensus guidelines for HCV management [4,5]. A phosphoramidate prodrug, sofosbuvir’s pharmacological action relies on intracellular hydrolysis to a triphosphate active form, which binds to the nucleotide binding site of the NS5B, the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase of HCV [6,7]. The 2-fluoro-C-methyl moiety binds to the active site of NS5B, acting as a potent chain terminator [7]. In Harvoni® sofosbuvir is combined with ledipasvir, which inhibits the NS5A protein of HCV [7].

The causal link between HCV and PHTN is unclear. Several in vitro and experimental studies demonstrate that non-structural (NS) proteins of HCV, particularly NS3-NS5A/B, can lead to activation of the Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3 (STAT3) axis implicated in the pathogenesis of PHTN through its role in regulating cell proliferation, acute inflammation and apoptosis [7–9]. In experimental studies, the expression of these NS HCV proteins induces the expression of cyclooxygenase-2, producing increased levels of proinflammatory cells such ad prostaglandins, and induces oxidative stress through dysregulation of intracellular calcium [9–12]. In vitro inhibition of HCV replication using marine algae, Gracilaria, showed decrease in inducible nitric oxide synthetase and COX-2 gene expression [13]. This suggests that sofosbuvir’s action in binding to NS5B leads to rapid decrease in vasodilatory mediators, acute inflammation via activation of COX-2 and increased smooth muscle proliferation, leading to development of PHTN [14,15].

The presence of potentially confounding comorbid illnesses has increased the complexity of establishing the true relationship between sofosbuvir and PHTN in these patients, but the body of work demonstrating this association is increasing [16]. This patient presented with comorbidities that could contribute to PHTN, however these are more likely to produce chronic changes with gradual onset rather than an acute deterioration. Firstly, smoking may be a risk factor for PHTN [17]. Secondly, the causal relationship between OSA and PTNH remains abstruse, due to the small numbers of patients. Several small cohort studies investigating causality estimated PHTN prevalence in OSA at 12%–34% [16], and OSA in PTNH as high as 89% [18]. The pathogenesis is probably related to irreversible vascular remodeling and modulation of vasoactive agents, namely endothelin-1, platelet-derived growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor [14,15,19]. However, the PHTN is usually mild, and the process itself is chronic and thus, seems unlikely to solely cause an acute presentation seen in this case [20]. Additionally, this case displayed no evidence of POH or cirrhosis on abdominal ultrasound to implicate alcoholism causing PHTN.

A prospective registry of patients initiating sofosbuvir with baseline echocardiographic assessments of pulmonary function would help answer this question. The implication, if causality was established, would be prescreening patients for PHTN prior to starting therapy. With ongoing follow-up post-therapy, atrisk groups would require consideration of alternative agents if prospective data showed functional decline with worsening WHO classification. This paper adds to the mounting evidence that this link needs to be explored prospectively.

Keywords

Hepatitis C; Sofosbuvir; Right heart study; Direct acting antivirals

Cite this article

Nolan M, Bhindi A, Kilpin M, Jeganathan V, Fisher L, Chimunda T. A case of pulmonary arterial hypertension secondary to hepatitis c treatment with ledipasvir/sofosbuvir combination. Clin Case Rep J. 2020;1(1):1–4.

Copyright

© 2020 Timothy Chimunda. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY-4.0).